Read Time 5 Minutes

I’ve been trying to determine the secrets of pedal board hookup for quite some time – in just what order should your pedals be for best results. I have combed the depths of guitar forums, websites, the brains of friends (that was scary(!)) and asked a million questions trying to find what works the best. What did I find out, you ask? In a nutshell… nothing!

Well, that’s not strictly true. I found out that there are as many varying opinions as there are experts to ask, and lots of unsolicited advice from self proclaimed experts that should be taken with a huge grain of salt, mainly because they are clueless.

So… what does a guitar player, who really doesn’t want to get an electrical engineering degree, do to figure it out? Perhaps the best advice I got was to hook up your pedals and see how they sound. Then swap them around and try again. Keep it up until you find the best combination. (I sure do long for the days when you had a wah and a fuzz connected to the front of a Fender Dual Showman or a Vox AC30 Top Boost and were blissfully ignorant of any interaction between them! You just played.)

Since I have become the go-to guy for DIY projects here on Guitar-Muse, I’m going to attempt to set everybody straight on this subject in clear and simple terms. I’m also going to try and tell you why certain things happen in the signal chain so you can troubleshoot your setup when you add or remove pedals. I’m going to do this over several posts so it won’t become unbearable in one sitting, giving you just enough electrical theory (hopefully, in terms you can understand) to drive home the reason some things work one way and not others. (Rats! I’m already confused!)

Lesson One – All Pedals Are Not Equal:

Most of you should already know this but, just in case, here’s a short primer on power requirements.

Most of you should already know this but, just in case, here’s a short primer on power requirements.

The vast majority of simple pedals will run on one, or two, nine volt batteries. This was the de-facto standard until a few years ago when replacing the batteries before every gig got old, not to mention expensive, and pedal power supplies became widely used. (I had to modify 2 of my old pedals to accept pedal power – no jacks.) The standard pedal power is 9 volts DC (Direct Current), with the positive being on the sleeve and the negative being in the little hole in the center of the plug (the tip). This puts the actual power the pedal is using at -9volts DC. See Pic 1 to be clear. This means that you can’t buy a wall wart from Radio Shack and use it as a pedal power supply as you will find few of them that have the negative on the tip, nor will you find many with enough current output to power more than 1 or 2 pedals. See how the manufacturers got you? You gotta buy something designed to power pedals.

Lesson Two – AC vs. DC:

Some wall warts will not provide DC but are AC (Alternating Current – like the sockets in your house but lower voltage) and won’t do anything but fry your pedals. Bottom line: stay away from the common wall wart and save yourself some grief.

You will find pedals requiring 9, 12, 18 and 24 volts DC on the market. The higher voltage ones may come with their own wall wart and should be plainly labeled so you know. Once you have the voltage requirements of your setup figured out, you can look for a commercial power supply to provide what you need. Many of the supplies on the market will have provisions for multiple voltages as well. Buy the best you can afford. You will find pedals that run on AC current and even have a traditional two-pronged plug. (More about that later.)

Lesson Three – Current:

The standard, run-of-the-mill pedal will require from 3ma to about 60ma (or so) but some pedals, primarily digital pedals, may need up to 150ma. (ma = MilliAmps or 1000th of an amp. For example: if you have 6 pedals, all drawing 50ma, that’s 6 X 50 = 300ma, or .300 amp. A one amp supply will power those with no sweat.)

You will need to add up all the current (the amount of electricity the pedal requires flowing through it for proper operation) needed by your pedals so you can determine what level the power supply has to provide. Don’t be fooled into thinking that if the pedal is off, it isn’t using power… wrong. All pedals that are plugged in to the supply are drawing current all the time, you just switch them in and out of the signal chain. Some of them may lessen their needs when not in the chain but they are all “on.”

Add all the current needs together and then add half again as much (in the previous example, add another 150ma, for a total 450ma or .450 amp) for a cushion. You want your supply to “easily” provide the power to avoid overheating and so you can add a pedal or two without overtaxing your supply.

Lesson Four – Ground Loops:

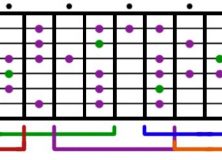

The vast majority of us use a power supply that “daisy chains” the pedals together (yep, that includes me). By necessity, these supplies connect all the power grounds together and will wind up with the signal ground (the sleeve on your 1/4″ audio plug) attached there, too, either directly or through a metal case. (My regular readers will remember I had some trouble with this when modifying my MOD Kits DIY Trill Tremolo for a power supply.)

This is “no big deal” when you have a couple of pedals from one manufacturer but, add in a boutique pedal or two, or heaven forbid, a vintage germanium transistor pedal (I’ll explain that sometime), and now you have a whole separate signal path whose only purpose in life is to make your sound suck! This is called a ground loop and is to be avoided at all costs (unless that sucky tone IS your sound(!)).

The way to avoid this problem is to have isolated power, ideally, a separate power wire for each pedal. That gets a little extreme, in my opinion, with modern pedals being power isolated pretty well. You will find pedals that don’t adhere to this practice well, mainly vintage ones, and you’ll notice an increase in noise (or any number of other problems) when you plug them in. Usually, any pedal that is using a plastic socket for your power connection has enough isolation to avoid a problem when plugged in… usually.

To test for a ground loop, plug in your pedals one at a time, listening for noise. When you find it, determine what’s causing the noise before you go on, or eliminate the pedal for now and continue testing your other pedals. You will usually find that the offending pedal(s) are shorting your power ground (+) to the audio ground (-), degrading your signal or causing hum (or noise). You can only try to isolate the power ground from the pedal’s metal case (the usual culprit) but that can be an ordeal on older pedals. You can try providing that pedal with its own supply, separate from the rest of your pedals. That will sometimes remove the offending pedal from the ground loop but, if you have the power ground to audio ground problem, it’s tough to make that pedal work with your others. A battery for that pedal may be necessary.

Next time, we’ll continue on with bypass or buffering, and we’ll talk about effects loops. Until then…